Archaeological Photography

The role of archaeological photography for recording archaeological excavations remained common throughout the nineteenth- and twentieth- centuries, although, the scope of documentation changed with the onset of large-scale excavations. The objective from then on has been to transform photographs of sites into quantifiable documents, and establish an imagery that can be compared. The best examples with respect to South Asian archaeology are those that were created for the excavations undertaken by Mortimer Wheeler, the last British Director General of the Archaeological Survey (1944–1948), and they pose a striking contrast to those that were taken during Marshall’s directorship (Figures 17 and 18). Wheeler used his excavation photographs to impress his audience with his highly controlled and nearly ‘perfect’ methods, which he believed was his unique legacy to South Asian archaeology.

The role of archaeological photography for recording archaeological excavations remained common throughout the nineteenth- and twentieth- centuries, although, the scope of documentation changed with the onset of large-scale excavations. The objective from then on has been to transform photographs of sites into quantifiable documents, and establish an imagery that can be compared. The best examples with respect to South Asian archaeology are those that were created for the excavations undertaken by Mortimer Wheeler, the last British Director General of the Archaeological Survey (1944–1948), and they pose a striking contrast to those that were taken during Marshall’s directorship (Figures 17 and 18). Wheeler used his excavation photographs to impress his audience with his highly controlled and nearly ‘perfect’ methods, which he believed was his unique legacy to South Asian archaeology.

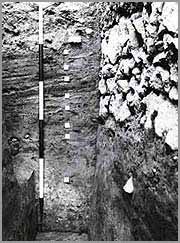

The extent to which Wheeler regulated visual information by forcing his readers to see what he wished seen, makes the photographs, such as Figure 19, akin to those of specimens of the natural and biological sciences. Such an imagery of excavation effectively erases “the troubling spectre of intimacy” (Poole 2005, p. 166), to render a science in action. Thereby, they also alert us of a discipline in transformation with respect to its aims and self-definition (see Guha 2003).

Disciplinary transformations have often involved the making of unique archives, and here Marshall’s efforts are worthy of notice. In 1904, Marshall proposed for the establishment of a distinct photographic Fig: 19 archive, the D.G.A.’s,for the Archaeological Survey of India, within the precincts of its headquarters, then in Simla (for details Guha forthcoming). In sharp contrast to Forbes Watson’s view, that an archive of architectural photographs “will probably constitute the most valuable work on art produced in the present century” (1869, p. i), Marshall suggested that since many of the “pictorial illustrations, the reproductions, the plans, and the sketches …have been prepared in England; some in Madras; and some in other parts of India or Burma. They are to be appraised independently according to their unequal individual qualities, and not viewed as a single artistic whole” (1904, p. 13). Marshall’s remark inevitably brings to mind the distinction, which Fergusson had drawn between his own sketches and those of the Daniells’.

Disciplinary transformations have often involved the making of unique archives, and here Marshall’s efforts are worthy of notice. In 1904, Marshall proposed for the establishment of a distinct photographic Fig: 19 archive, the D.G.A.’s,for the Archaeological Survey of India, within the precincts of its headquarters, then in Simla (for details Guha forthcoming). In sharp contrast to Forbes Watson’s view, that an archive of architectural photographs “will probably constitute the most valuable work on art produced in the present century” (1869, p. i), Marshall suggested that since many of the “pictorial illustrations, the reproductions, the plans, and the sketches …have been prepared in England; some in Madras; and some in other parts of India or Burma. They are to be appraised independently according to their unequal individual qualities, and not viewed as a single artistic whole” (1904, p. 13). Marshall’s remark inevitably brings to mind the distinction, which Fergusson had drawn between his own sketches and those of the Daniells’.