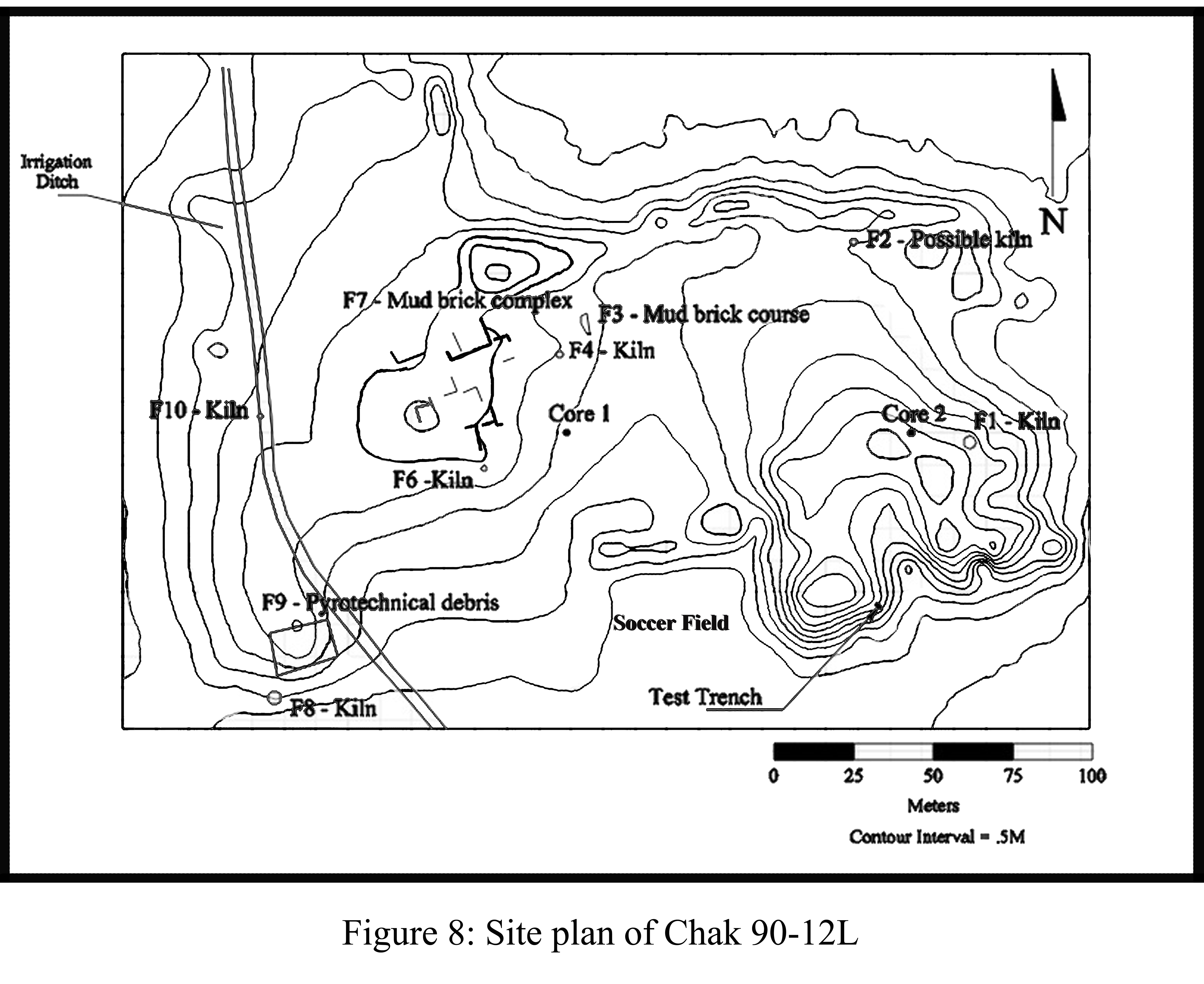

The site of Chak 90-12L is one of the larger sites found along the Beas, at 7.5 hectares. Figure 8. It is surrounded by housing and cultivated fields and has undergone significant modification since the time of its first discovery by the PAS and the two visits the Beas team made to the site. Tractors are the principal earth moving device.

During our first visit we noted clearance activities that leveled the landscape when a soccer field was built. This activity destroyed a portion of the mounded area of the site. Additionally, local farmers had been granted government permits to develop the land and tractor activity led to trimming at the margins of the site to increase the size of fields. Other changes were noted on a subsequent visit the following year, when a house was built along its eastern face (not shown on the map) and a deep trench dug through the western part of the site (recorded on the map). Local people informed us that the trench was built for irrigation purposes but it appeared to be ineffective, as it showed no signs of use.

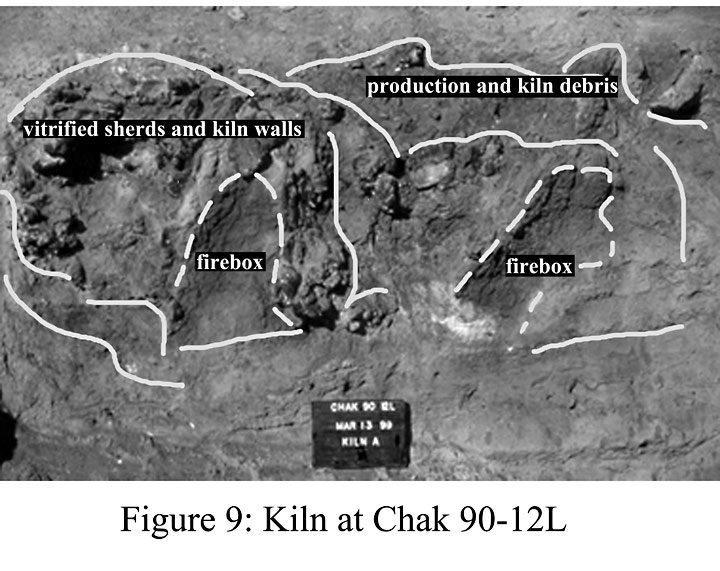

In spite of this destruction, study of this settlement was important because it featured a setting that was nearly identical to Lohoma Lal Tibba (to be discussed below) and other Beas sites, though not Vainiwal since it does not have a late Harappan occupation. Chak 90-12L is built up along the fertile floodplain of the Beas and based on the stratigraphic interface between its cultural and natural levels, the site developed during the Early Harappan, when Harappa was expanding in size. This interpretation complements surface indicators in which there are large quantities of Early Harappan artifacts, not previously noted by the PAS, since they are limited to a small section of the settlement. In the Harappan the entire surface is covered with Harappan material remains, again indicating, as at Lohoma Lal Tibba, an expansion at the same time that this occurred at Harappa. In addition, we were able to plot a complex of mud brick houses and numerous craft activities associated with the Harappan period. We also discovered numerous pyrotechnical activities including the surface remains of kilns and manufacturing debris, at several locations. One of the kilns, F10, was cut through in the process of digging the irrigation trench. Although damaged and collapsed by the tractor cut shown on the site plan, heavily vitrified kiln walls were discernible as shown on Figure 9.

Other kilns were identified based on vitrified walls, wasters and firing debris. A single stratigraphic exposure was examined at the site of 90-12L. A stepped trench was extended to a depth of 1.9 m and revealed a sequence analogous to those identified at smaller mound sites along the Beas. Typically such sequences expose a basal alluvium upon which evidence for cultural sedimentation is variously preserved. As discussed elsewhere (Schuldenrein et al, 2004) “transitional horizons” are very well preserved at such sites and these document the nature of site formation process at locations where an initial phase of site selection (by the earliest Harappan residents) is registered by a poorly sorted admixture of churned cultural sediment and alluvium. The cultural matrix may be stratified or represented by isolated evidence of human utilization, either in situ or locally displaced. The cultural deposits are then capped by various thicknesses of colluvium that are the product of long term mobilization of sediment during post-abandonment stages.

At 90-12 L undisturbed and massive alluvial silts form the base of the sequence (1.5-1.9 m). These are unweathered and unconformably overlain by an intergraded matrix of cultural debris and alluvial silts (1.0-1.5 m). The latter are discontinuous and feature inconsistent structural integrity, as they were locally disrupted by perturbation processes (sources are unclear, but related to anthropogenic modification to the formerly extant surfaces). The cultural sediments are dense and laterally heterogeneous (0.4-1.0 m). They represent ashen fills as well as looser interdigitations of artifact fragments and reworked sands, silts, and gravels. The ashen fills are in situ, reflective of burning episodes. They are effectively palimpsests. The parent cultural materials in this sediment are poorly sorted and represent irregular redeposition. This primary cultural fill is covered by a “transitional horizon” (0.2-0.4 m) that has been extensively reworked, probably immediately after site abandonment. The capping sediment is poorly sorted hillslope colluvium and was laid down after most recent recontouring of the landform.